No products in the cart.

Explore

Contact Us.

We're ready to help.

Looking for more information, or to be connected with your local representative?

We can help. Fill out our contact form to get started.

25

Apr

Myths Debunked! How Lymphatic Imaging is Changing Patient Treatment Plans

By Caroline Fife, MD and Eva Sevick-Muraca, Ph.D.

This is a 22-minute read.

Editor’s note: This article is based on a webinar about the same topic. Access this webinar and watch more videos from the Lympha Press Education Series on YouTube.

The more we know about the lymphatics, the more obvious it is that our health is dependent on lymphatic function for both fluid homeostasis and response to infection. Our immune system is the body’s waste management system. It’s also essential to our cardiovascular health. However, despite its vital functions, the lymphatic system has largely escaped clinical investigation because until recently there has been no way to look at it easily.

When I [Dr. Caroline Fife] was running a wound center at Memorial Hermann, the UT Health Science Center in the Texas Medical Center, women with post-mastectomy arm swelling kept calling me to ask if I took care of lymphedema patients. Initially, I kept saying “no,” but fortunately these women were persistent. I thought to myself, “I know something about edema and venous disease. Why not learn a little bit about lymphedema? How hard could it be?”

At the time there was only one textbook. We hired some amazing lymphedema therapists who were my primary teachers. However, I noticed that many times the patient’s history and clinical presentation did not follow the textbook! There were many things that just did not make sense based on our understanding at the time.

In addition, the only way to get anatomical information was by performing excruciatingly painful, and somewhat dangerous, dye injections that could further damage the lymphatics and required putting a needle into a lymphatic vessel. This was around 1999 or 2000, but it felt like the Victorian era. The diagnosis of lymphedema was made by clinical examination, after which we could put patients in lymphedema bandages, but we did not know what the actual problem was with the lymphatics, and that meant there was no way to develop other types of treatments or medications.

I had so many questions: Do patients with primary lymphedema have a normal number of lymphatics that just don’t function? Or do they not have lymphatics? Why do the majority of patients with chronic non-healing wounds have lymphedema? Why can some patients develop horrible lymphedema after minor trauma or minor surgery, while some patients in the days of radical mastectomy did not develop severe lymphedema?

Around 2002, out of the blue, I got a phone call from Eva Sevick. Eva explained she was developing a relatively non-invasive, real-time lymphatic imaging technology. She’d heard that I might have a few patients. By then, I actually had a LOT of patients. In fact, just through word of mouth, our lymphedema program had become a huge clinic. Eva will now explain how the imaging process works.

How Lymphatic Imaging Technology Works

Typically, my team will inject a “microdose” of indocyanine green dye, also known as IC-Green or ICG, and allow it to be taken up by the lymphatics. We are talking about the amount of dye that is so small, it’s unlikely to cause any effect whatsoever, except to be able to visualize it within the lymphatics using the imaging system we developed. The dye is injected beneath your skin in the same way as you’d get in an allergy skin test or a TB skin test with one of those tiny needles that prick the skin. Immediately after injecting this tiny amount of dye, it is possible to see the lymphatics pumping the dye-laden lymph to move fluid back to the heart.

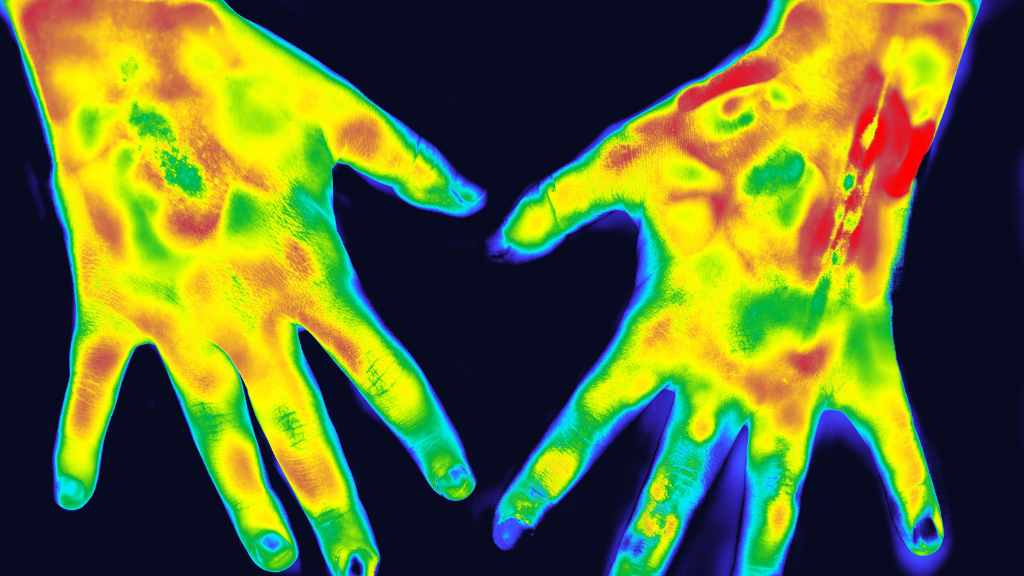

The imaging uses a low-power laser light similar to the grocery store scanner used to tally the cost of your groceries. When the dim light shines on skin, it penetrates the tissues, and the IC-Green within the lymphatic vessels generates a light of a different color. This different color light (or fluorescence) travels back to the skin surface where we filter out all other light and collect the fluorescent light with our imaging system.

The imaging system uses a silicon chip array, like the one used in your cell phone camera, to collect these images. Right before the silicon chip array, we place a military-grade, “night-vision” intensifier that magnifies the light so that the silicon chip array can detect the fluorescent light more sensitively. This night vision technology is the “secret sauce” for the lymphatic imaging that we conduct.

The IC-Green dye emits fluorescence in the near-infrared wavelength range, so that after we inject dye under the skin and allow the lymphatics to take it up, we can image the vessels beneath the skin. High doses of IC-Green into the skin can leave a permanent green tattoo. Our more advanced camera technology is so sensitive that we can use extremely small amounts of dye—far, far less than at the tattoo parlors! These small amounts of dye won’t overwhelm the lymphatics yet will still allow us to see what’s happening inside someone’s body as the lymphatics are pumping. Once the IC-Green leaves the lymphatics, it goes to the bloodstream where it is rapidly cleared from the body through the liver.

Insights Into the Lymphatic System

These images showed us how the lymphatics were operating inside the body and have revolutionized our thinking. There’s so much we didn’t know. For example, we knew the lymphatics pumped fluid, but did they pump in time with the metronome of the heart? How did the breathing rate affect their pumping? How did massage affect their pumping?

It was like we were discovering a new world. It was an exciting moment. It still feels that way to do imaging studies and discover new things about the lymphatics.

It’s particularly exciting to think about the benefits for pediatric patients. Generally pediatric patients need to be sedated for imaging, and we generally don’t like to give kids radioactive tracers. Because the near-infrared lymphatic imaging system takes several pictures per second, infants and children do not need to be sedated. In addition, IC-Green is not radioactive.

The medical community also likes this procedure because it’s a “microdose” of contrast agent; meaning, it’s such a tiny, trace amount that it has no pharmacological action. It’s a simple technique, and injection isn’t very uncomfortable. People who have had other types of lymphatic imaging (such as lymphoscintigraphy) tell us they prefer our procedure because it’s not traumatic for them in comparison. Unlike these lymphatic imaging technologies, the injection is not painful, and patients are typically fascinated watching their lymph move in real time.

One important thing we’ve learned is that everybody’s lymphatics are different. You can open a textbook and see a picture, but everyone’s lymphatics pump differently. If they stop pumping, you’re not moving fluid, then this will lead to increased fluid volume in your tissues and lymphatic dysfunction.

Because images are taken so rapidly, we can quantify the pumping rate of the lymphatics. Most clinicians and patients know that certain drugs make tissues swell. Well, besides those drugs that impair lymphatic function, there are probably drugs that can make lymphatic function better! Measuring the volume of a limb with a tape measure isn’t a sensitive enough way to quantify the effect of a drug on lymphatic function. We must be able to quantitate whether or not the lymphatics are pumping normally. This technique opens the door to drug therapy because we can measure in a very objective way whether a drug improves or reduces lymphatic function.

Busting Lymphatic Myths With New Imaging Studies

You may have read in a textbook that the lymphatics don’t cross the midline of the body. In fact, unlike the blood circulatory system, the lymphatics are unidirectional and organized into lymphatic watersheds. It’s been assumed that these watersheds are separate and distinct, and lymphatic vessels do not cross between these watersheds. “Stay in your own lane.” Or, in terms of lymphatic vessels, “stay in your own watershed.” This has been a long-held belief among therapists. It has huge implications for cancer metastasis, for example, because what if left breast cancer can metastasize to the right breast? It also has implications for manual lymphatic drainage techniques wherein massage is directed to move lymph within a lymphatic watershed.

News flash: The lymphatics cross the midline. In fact, our studies show that they regularly cross the midline and across watersheds. Our body “regrows” lymphatics after injury, trauma, or certain diseases, and when these lymphatic vessels grow through a process of “lymphangiogenesis,” they don’t respect the confines of the watersheds.

In one patient with head and neck cancer, we could see from the IC-Green studies that the lymphatic drainage from the front of the head wraps around the neck and crosses the midline into a different watershed. In another patient with similar cancer, a short movie we made shows the pumping action from the side of the head that was treated with radiation to the side without radiation treatment.

We had a patient with tongue swelling and squamous cell cancer. He had two primary cancers treated with surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. He had terrible functional problems after all of this and couldn’t swallow. We were asked if we could image him to find out which lymphatics were open, to direct massage therapy. The myth that the lymphatics weren’t crossing the midline could have prevented proper treatment for this patient.

There’s also another myth involved here, which is that the lymphatics don’t grow across scars. When you look at the images of the aforementioned patient’s face where we did the IC-Green injections, you can see that the lymphatic vessels drained down into the clavicular lymph nodes and the jugular chain. The patient had a v-shaped scar on his neck, and the lymphatics were crossing that scar. He’d had numerous surgeries with numerous scars, so this was a significant issue for him.

What about manual lymphatic drainage (MLD)? Often, we hear therapists say, “There’s no point in doing MLD over a scar because fluid won’t go there.” With this new knowledge, we now know if there’s a route that could be valuable to the patient, don’t avoid it just because there’s a scar.

Now let’s consider swelling. The therapist may say they can feel a patient’s lymphedema even before they get swollen and can tell their lymphatics may have a problem. I (Caroline Fife) used to laugh at this idea, and yet thanks to ICG imaging, we know that lymphatic dysfunction starts long before clinically apparent swelling.

In a study of advanced breast cancer patients treated with axillary lymph node dissection and radiation treatment, clinicians imaged the lymphatics before and after cancer treatment. After radiotherapy and at six-month intervals, these patients had their arm lymphatics imaged with the IC-Green and our lymphatic imaging system.

In these patients, dermal backflow was an indication of lymphatic dysfunction, as dermal backflow actually occurred before any visible swelling. What we believe is happening is that lymphedema develops because the intrinsic lymphatic pump fails. There’s not enough pressure to push the fluid forward through the lymphatics, thus there is “backflow” and leakage of lymph into the tissues. This is clearly shown in the imaging studies.

As a result, there’s a pond effect where the fluid pools. Picture a vacuum cleaner that’s too full and isn’t being emptied, so it stops sucking. Suddenly you realize it’s leaving dirt behind or even blowing dirt out into other areas. Same is happening before the onset of swelling and lymphedema.

In a total of more than 700 patients that we imaged, we could ascribe this dermal backflow to lymphatic dysfunction and to current or future risk of lymphedema. This means dermal backflow may be the first harbinger of lymphedema (and not a late one). Although this has been suggested by others before, this is the first time longitudinal lymphatic imaging measurements have bolstered the idea.

If you use dermal backflow as a predictor for lymphedema, we think that you may be able to predict the onset of visible symptoms of lymphedema as much as 8 to 24 months sooner. From there, imagine what you could do if you could treat those patients before irreversible tissue damage sets in. Perhaps it’s possible that we could even ameliorate the condition of lymphedema if we started treatment early enough.

Further Reasons for Lymphatic Imaging

There are other reasons we need to use imaging. For example, we can use lymphatic imaging to prove that once lymphatic dysfunction does exist, a patient may benefit from a lymphatic pump. Without a way to confirm the diagnosis of lymphatic function, insurance companies and patients may feel that they are being asked to buy and use a device that they don’t really need. Now we have an objective imaging test to show that they truly need treatment now before it’s too late.

Some healthcare professionals, particularly back in the 1980s, believed pneumatic pumps were ineffective or might even damage lymphatics. After using a pneumatic compression device on some patients, it’s clear that the IC-Green dye is moving. The transport is either extra vasculature or is within the lymphatic vessel, but nonetheless, it’s moving the lymph out of the affected tissues.

Lymphatic imaging has helped to convince Medicare that pumps are needed and that they work. Similarly, some therapists believed that exercise was not good for lymphedema patients. We’ve shown that exercise can enhance lymphatic function.

Interestingly, some therapists have claimed that if they do MLD on the left arm, the lymphatics in the right arm will pump faster. This might sound unbelievable. However, imaging studies do indeed show that when you massage one arm, you’ll see lymphatic pumping increase in the other arm. Also, when the patient does deep breathing, you can see the lymphatic pumping action occurring. Now we see through imaging studies that during MLD, the lymphatic pumping starts. We’ve been able to show that when therapy begins, there is a clear increase in lymphatic pumping in response.

What about when a payer is questioning payment? It’s challenging to make a convincing story about the benefits of MLD based on girth measurements, but we can now prove it with imaging.

Consider a study with a patient who was treated early to see what would happen with the dermal backflow. We did injections before and after on the mandible, and we could see quite a nasty-looking dermal backflow. It’s going up, rather than down, meaning the swelling is headed in the wrong direction towards the face. We put this patient on an advanced pneumatic compression device, and after a 30-minute session, we could see improved drainage to the cervical lymph node on the way down to the clavicle. We sent this gentleman home with the device for two weeks of at-home treatment, and after that, the dermal backflow was gone. We also saw reductions in dermal backflow and improved lymphatic function in 6 out of 8 patients who had two weeks of at-home treatment, but their lymphatic dysfunction continued. Whether longer treatment sessions, or treatment for additional weeks, ameliorate lymphatic dysfunction remains to be studied.

It makes you wonder what would happen if we treated cancer patients in the weeks following radiation therapy? If we treated them early, could we prevent the lymphatic dysfunction that eventually leads to irreversible tissue damage? Imagine a world where we never have to treat lymphedema again because it never develops. We need a lot more research to determine that, but we have the technology to prove or disprove it.

Currently, there are lymphedema cases where it’s difficult to determine whether the person has venous or lymphatic disease. For example, we studied a teenager with swelling in her right leg who had a stent placed because they thought she had a venous disorder. When we imaged her, we saw that the so-called normal leg had very dilated lymphatics. But the abnormal leg had the dermal backflow.

It’s hard to say for sure whether this patient had venous disease before stenting, but we might suspect that it was probably primary lymphedema—a lymphatic disorder that does not appear to be caused by trauma or cancer treatment. Because the imaging showed deep lymphatic vessels pumping, we arranged immediate MLD and compression.

Think about what this could mean for a teenager. Instead of going 20 years untreated, perhaps eventually becoming completely disabled, we can get a jump on lymphedema treatment and prevent the worst outcomes.

This is an important point because it touches on the mythical idea that lymphatic function is the same in everyone. We are not all created equal from the standpoint of our lymphatics.

In a way, it’s become even trickier to understand what abnormal is. In the old days, there were radical mastectomies where the surgeons took out every lymph node they could find, and some women still didn’t have much swelling. On the flip side, there have always been women who have only a small procedure like a sentinel lymph node biopsy and develop lymphedema. Today, we can see the lymphatics in so much more detail, but we still don’t know why there’s so much variability among people.

In one case, a patient was an opera singer who was upset that her swollen hand was very visible to the audience from the stage. We did an injection on the top of her hand, and it pumped into the fingertips. When she turned her palm over, what she thought was sweat was actually oozing lymphatic fluid. As it turned out, she had primary lymphedema which had not become clinically apparent until she had breast cancer.

We sometimes hear from women with breast cancer who are being offered two options: breast removal or minimal surgery with radiation. The outcome is predicted to be the same from the standpoint of cancer. Wouldn’t it be wonderful to be able to predict whether one option would be better, from a lymphatic standpoint?

We don’t have enough data to be able to direct people making these decisions. However, we do have enough data to show that some patients do not have “typical” lymphatics, by historic standards, from the outset, and they may have considerations that would impact their choices. We’d like to be able to provide these patients with firm answers, but we simply can’t do that quite yet.

In Summary

Imaging studies are debunking many myths about lymphedema as they teach us more about the internal workings of the body. We now see, with stronger evidence than ever, that early intervention may reduce the severity of clinical presentation.

So many patients have lymphedema due to non-functioning lymphatics, where the lymphatics are present, but they’re not pumping properly. It’s exciting to think about the possibilities of helping these patients access early interventions that improve their lifetime health outlooks.

In closing, we’d like to wrap up by acknowledging the lymphedema therapists who claimed for so long that lymphedema crossed the midline, along with other bits of wisdom. They were right after all.

About the Authors

Caroline Fife, MD, FAAFP, CWS received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Texas A&M University College of Medicine. She worked in family medicine at the University of Texas, Southwestern, and served as a member of the faculty of the University of Texas Health Science Center in Houston for 23 years and is now a professor of Geriatrics at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, TX.

She initiated the renowned Memorial Hermann Center for Wound Healing and the Memorial Hermann Center for Lymphedema Therapy and is currently the Medical Director of the St. Luke’s Wound Clinic in The Woodlands, TX. She’s also the CMO of Intellicure, a Texas-based software company, as well as the director of clinical research for the U.S. Wound Registry. She worked with Eva Sevick to develop real-time lymphatic imaging.

Eva Sevick-Muraca, Ph.D. is the Nancy and Rich Kinder Distinguished Chair of Cardiovascular Disease Research at the University of Texas Health Science Center’s Institute of Molecular Medicine (IMM) and is the director of the Center for Molecular Imaging. She received her Ph.D. in Chemical Engineering at Carnegie Mellon University, her post-doctoral training in Biochemistry and Biophysics at the University of Pennsylvania, and served on the faculties at Vanderbilt, Purdue, Texas A&M, and Baylor College of Medicine. She is a past recipient of the National Science Foundation Young Investigator Award, the National Institutes of Health Research Career Award, and the American Cancer Society Research Scholar Award and has served as an appointed member of several NIH and DOD study sections, associate editor of the IEEE Transactions of Medical Imaging, and officer of the Society of Molecular Imaging.

Dr. Sevick-Muraca pioneered the development of near-infrared fluorescence optical imaging and tomography for molecular imaging. She has two clinical trials underway at the University of Texas Health Science Center and Memorial Hermann Hospital employing the technology for novel diagnostic imaging of lymphatic function.

About Lympha Press

Lympha Press addresses lymphatic diseases and conditions by improving lymphatic fluid flow within the body. Clinicians and patients are welcome to explore Lympha Press therapy options. These products offer significant lymphedema symptom relief with results backed by clinical studies.

Share this post

Related Posts...

Explore

Contact Us.

We're ready to help.

Looking for more information, or to be connected with your local representative?

We can help. Fill out our contact form to get started.